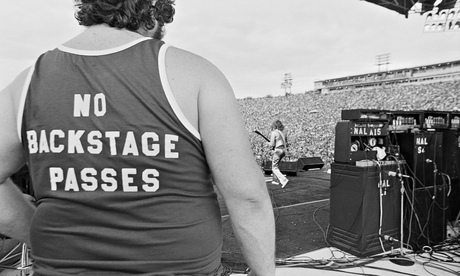

Before the live-music industry became a billion-dollar behemoth, being on the road was, for many bands, a wild west of sex, drugs and even some rock'n'roll. Hedonism was rife, and it wasn't just the musicians who pillaged. Their road crews were right there with them, benefiting from a macho atmosphere where the expectation was that after they had unloaded the gear they would match their employers in debauchery.

Some roadies became famous in their own right. Led Zeppelin's tour manager, for one: there's a Richard Cole Appreciation Society on Facebook, glorifying the man who was, according to the unofficial band biography Hammer of the Gods, "responsible for much of the mayhem" around the group. Then there was a metal roadie called Jef Hickey, who carved out such a reputation that half an episode of Vice.com's 2011 documentary series, On the Road, is devoted to him. Rock musicians speak of him in awed tones: "One time we were on a plane, and he went up to this stewardess and asked her if she had any drugs," claimed former Queens of the Stone Age bassist Nick Oliveri – and that was only the most printable of Hickey's antics.

Roadie annals are full of such stories, many of them involving unpleasant treatment of female fans. But that era has long passed, and with it the idea of roadies as folk legends. They have since osmosed into "techs" – low-key professionals who often have degrees and treat the job as a job. "Bad behaviour isn't acceptable any more, to be drunk and carrying on," says Chris McDonnell, the Charlatans' sound engineer. "A lot more is expected of you. People think it's crazy backstage, and it's girls and drugs, but it's not. It's people working and having a cup of tea."

With the biggest acts generating mammoth box-office receipts (last year's top tour, Bon Jovi, grossed $205m), unprofessional behaviour is likely to result in the sack. "You have to pay for hotel damage now. I've certainly thought of throwing the TV out the hotel window, but I couldn't afford it, and would get fired," McDonnell, 23, says. And the musicians are more responsible; on the phone before a show in Germany, Max Helyer of You Me at Six, Britain's biggest pop-metal band, says bluntly: "[The crew] are here to do a job, and we don't get destroyed out of our faces, because that would let down people who've paid money to see us."

But if techs have become more abstemious and less visible, it's brought them closer together. Being the backbone of the live-music business generates a particularly intense camaraderie. Roadies socialise – there's an annual convention; they have dedicated websites and they speak their own lingo ("shitters", for example, means "money" – supposedly invented by shoegaze band Lush's crew on a European tour in the 90s, when they were vexed by having to deal with multiple pre-euro foreign currencies).

But, despite the new clean-living techs, there are hints that things still go on that they can't talk about. Facebook tech pages tend to be closed to public view, and the biggest online tech site, Crewspace, accepts members by recommendation only. Crewspace's homepage assures its 16,000 members it's "a community where you don't get bothered by fans, etc", while its motto – "What goes on tour …" – hints at "colourful" discussions on its forums.

"I can't tell you the stories while my mum's still alive," says Crewspace member Roger Nowell, semi-jokingly. "[Touring is] a world of its own, but people won't write about what goes on, if they want to keep working." Which, of course, they do: for most, the job is a way of life, offering travel, a good income and the kudos of being part of an artist's inner circle. Nowell has been Paul Weller's guitar tech since 1999 – "I'm stage right, where he can see me, in eye contact" – and before that looked after "drums, bass and Liam's tambourines" for Oasis. But, like most of the techs I speak to, he makes a distinction between Then and Now.

Live music was once so unregulated, he says, that roadies coming home from 1970s American tours "would stuff dollars into [speaker] cabinets so they didn't have to declare them". Now, techs are tax-registered sole traders whose jobs have been transformed by technology. "It's not just stringing guitars now. It's all about programming and knowing how to …" He mimes tapping at a computer keyboard. Moreover, the younger techs are more health conscious – "They go running and swimming," Nowell says bemusedly – and some are even women.

Women are still massively under-represented, though: London-based sound engineer Anna Dahlin says that female techs are seen as a novelty. "It's not unusual to turn up at a venue with a band and get the question: 'Where's your sound guy?' And I wouldn't even want to start counting the amount of times I've got on to a stage and got the question: 'Are you the singer?' "

"It's not that the industry doesn't want females in it," counters Jon Bond, who's just spent seven months with Rudimental. "It's quite a scary job to go into, because it's dominated by males. The chat can be like a building site." With his BTec in music technology, he's typical of younger roadies, who get their foot in the door not by being mates with a band but by being able to run complex sound and lighting systems from day one. Bond is quick to add that the "chat" is just chat; crews know that "there's so much money in [touring], we have to take it seriously". And fans are off-limits: "The age of the people going to gigs seems to have got a lot younger, from 15 upwards, so bands don't want to be seen hanging around with those people."

Who do they want to hang around with? Each other, it seems. "It's not just a job – you're living very intensely together," says the Vaccines' tour manager, Nigel Brown, which explains why about 80 UK-based roadies, from newbies like McDonnell to veterans like Nowell, attend an annual invitation-only gathering. This year's was in January, in a bar in central London; within an hour of the doors opening, it was standing room only. One thing you could see from being there was that roadies don't necessarily look like roadies: for every denim-clad old-schooler, there was a clean-cut character who could have been a teacher. And they don't talk like roadies: there was little building-site chat, but quite a bit of bromantic bonhomie – and plenty of concern about the future. "There are so many bands on tour that you'd think there'd be more work, but in truth, it's much more streamlined now," said Nowell. He adds with a sigh that sums up the state of the music business: "It's expensive to tour."

• This article was amended 13 June 2014: Jon Bond was originally incorrectly identified as Jon Brien.