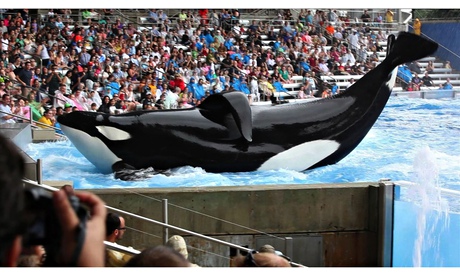

In four years’ time, Tilikum will move to a larger tank. Presumably frustrated by being confined to a tank in Orlando’s SeaWorld entertainment park, the killer whale has already been involved in the deaths of three people. Tilikum’s new home, announced by SeaWorld earlier this month, will be twice as big: 1.5 acres, 50 feet deep and 350 feet long. He’ll share it with the park’s nine other killer whales. Holiday-makers will still be able to watch the mighty and menacing animals up close, but they will be safe behind a 40-foot glass wall.

SeaWorld’s decision followed a consumer boycott and a dramatic drop in its share price, the result of Blackfish, a popular documentary that suggested Tilikum’s violence was a result of the conditions of his captivity. SeaWorld refutes the allegations made by former employees in Blackfish, arguing that the employees lack knowledge of today’s conditions and Tilikum’s care.

This isn’t the first time marine life and tourism have clashed. Following an outcry earlier this summer by travel writers and bloggers who will attend the TBEX travel conference in Cancun in September, organisers cancelled a dolphin tour. And this year Sir Richard Branson announced that Virgin Holidays will no longer do business with companies that take dolphins and whales from the wild.

“Tourism related to dolphins and whales such as orcas has been going on for quite a long time without many questions being asked,” says Chis Pitt, a spokesman for the conservation group Care for the Wild. “We love these animals, but we love them for our entertainment. There’s no way you’ll meet their needs if you have them in a pool or even a fenced-off section of an ocean.”

But, perhaps as a result of the growing awareness of animals’ intelligence, public concern over their life in captivity is increasing. Tilikum’s lethal attacks raise an obvious question: can tourism and wildlife ever co-exist, especially considering that tourism by definition means intruding on animals’ habitat and habits?

Yes, says Ronald Sanabria, the Rainforest Alliance’s Costa Rica-based vice president of sustainable tourism: “Our experience has shown us that tourism destinations can secure the sustainability, and in some cases the betterment, of [their] natural and cultural assets if the appropriate type of tourism is practiced.”

The global conservation group runs a sustainable tourism programme of its own, advising travellers on companies and destinations that will allow them to minimise their impact on wildlife and the environment while at the same time contributing to the local economy. Sanabria says: “We believe it is possible to conserve biodiversity and bring benefits to host communities through sound tourism development. The challenge is that not all destinations have access to information [that enables them] to go from sustainability theory to practice.”

Another challenge, of course, is that it’s simply not feasible for most of us to watch our favourite animals in their natural habitats. That’s why zoos and aquariums exist. And, from zoos’ and aquariums’ perspective, by keeping tourists away from sensitive habitats they also help conservation.

The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums bills itself as the world’s “perhaps largest conservation network”, and points out that its members have more than 1,000 species and sub-species in conservation breeding programmes. Many aquariums in coastal areas – such as Florida Aquarium in Tampa – assist local government by rescuing endangered animals, even measuring sharks’ stress levels.

But here’s a further complication: ambitious aquariums that try to replicate the wild as much as possible, for example by using wild corals, damage the ocean ecosystem in the process. The booming cruise industry has added a further layer to marine life danger: the enormous ships pollute the water and often dispose of garbage right into the oceans.

Care for the Wild notes that public aquariums – first introduced in the 19th century – are now a global tourism phenomenon, their number rising steadily despite the occasional boycott. (Dolphinariums, which house dolphins, are effectively banned in Britain as the high standards required make them unviable to run, but not the US.) The charismatic dolphins and orcas are a star attraction in the wild as well. In the Maldives, sharks alone generated almost $10m in tourism revenue last year. Increasingly, it is possible to enjoy the intelligent animals and their fellow water-based species without contributing to animal cruelty.

“The best thing to do is to go on a properly organised expedition where organisers understand that you can’t have many boats crowd around a single animal and you can’t follow the animals day after day,” advises Pitt. “And, while some zoos and aquariums do minimal conservation care, others do more. If you want to go to an aquarium, do your research. If you take five minutes out of your day, you can figure out whether they’re really working for the animals or just for the dollar.”

- This article was amended on 22 August 2014 to reflect that dolphinariums are not banned in Britain but are effectively banned due to the strictness of standards imposed.

- This article was amended on 27 August to correct the error that Tilikum is in San Diego. He is currently in Orlando.

Read more stories like this:

- Sustainable tourism: 10 key issues investors should consider

- How indigenous communities are driving sustainable tourism

- Six reasons why mass tourism is unsustainable

Join the community of sustainability professionals and experts. Become a GSB member to get more stories like this direct to your inbox