Should we boycott prawns? I have been asked that question repeatedly since the Guardian's investigation revealing the use of slaves in the chain that brings them from Thailand to our plates. The slavery we uncovered was no metaphor – we found trafficked migrants who had been bought and sold, and forced with extreme violence to work at sea for no pay for years. The fish they catch is used to make feed for intensive prawn production by the world's largest producer and supermarket supplier, CP Foods.

Is it right to eat products that depend on such fundamental abuse of human rights? Consumer boycotts have been influential in bringing about change – against the horrors of apartheid, for instance – but on their own they have absolute limits. Just because slavery has been found in part of the food chain, we should not delude ourselves that changing the shopping basket will be enough. And why stop at prawns when so many other supply chains, from soya to rare minerals, are founded on trafficked workers, and the World Cup infrastructure in Qatar is being built on exploitation that amounts to slavery?

And should it be down to us as individuals to fight these wrongs? The official and business response to the revelations of slavery in the prawn chain has been a curious mix of horror and laissez-faire. In the US – where we showed that slave-tainted shrimp is on sale in two of the world's largest retailers, Walmart and Costco – it looks likely that Thailand will be relegated to the lowest ranking in the state department's annual Trafficking in Persons report, due out on Friday.

In theory, that should trigger a downgrade in its trading status with the US, but in practice economic sanctions are generally waived when America's strategic partners are involved. Thailand's geopolitical position as a bulwark against instability in south-east Asia and the rising power of China is too important for sanctions with real teeth.

In the UK the nearest to government action we are likely to get is an amendment to the modern slavery bill. A provision requiring companies to check for slavery in their supply chains had been lobbied away by business. Now at least it stands some chance of being added by opposition MPs.

But clear political condemnation or forceful action has been woefully absent. Labour's shadow home secretary, Yvette Cooper, wanted the supermarkets to lead the abolition movement, and said it was up to them to stop buying prawns produced through the work of slaves. David Cameron, through a spokesman, said it was up to consumers. Both propose narrow, market responses to what they frame as a market issue.

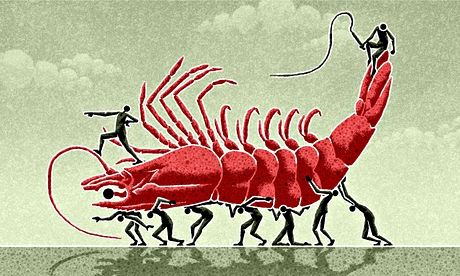

In doing so they reflect the real problem, which is that there's an enormous political deficit. They are drawing the politics of modern slavery in terms of consumerism – and a consumerism that is, moreover, seen as largely personal. The triumph of the global market and liberalism has promoted this individualism above social interests.

The genius of contemporary globalised capitalism is that it does not just meet demand, it creates new demand. It manufactures ever-escalating desires. Where once we might have wanted a healthy supply of fish, now we must have luxury fish as an everyday treat, even if it destroys ecosystems and enslaves workers. When the political discourse is as desperately reduced as this, all you are left with is shopping.

But that will not do. Globalisation of trade has created the potential for great new wealth but in many ways we have gone back to the dark days of the 18th and 19th centuries and the early industrial revolution – before workers were organised, and before laws were introduced to curb the excesses of the free market so that its contribution to overall affluence would not be undermined by squalor and suffering.

Supermarkets and the transnational producers are rightly in the firing line because in the unfettered market they are the ones with power: with turnovers larger than the national economies of many countries, they wield extraordinary influence. The fact that they do is part of the problem. However, most supermarkets have shown little sign of taking meaningful action on prawn slavery. They have made promises in the language of accountants and the balance sheet; they will audit and certify, because that is their currency. Just two have stopped buying – Carrefour, the largest retailer in Europe, and Ica in Norway – and the Thai stock exchange fell at the news.

So, a boycott has a place: it sends a message that hits the share price. But the real solution requires a different politics, one that rebalances power and restates the importance of the interests of the collective over the individual and the corporate – one that not only rescues workers enslaved at sea because they are victims but also gives them a stake so that they can unionise, as they have done elsewhere in the fishing industry, in order to tackle abuse.

For the rest of us, the solution may mean paying more or giving things up. And, meanwhile, no: I am not eating tropical prawns.